When

I was in my twenties, I wanted to be a man. Not literally but I had a lot to

prove and made sure that my paintings were as macho as they could be - big,

thick, dark, imposing and heavy. This is not to say that they were not sincere

and deeply felt. They were largely about fear and the manifestation of my

neuroses and my obsessive and perfectionistic nature.

I

did well in graduate school; after all, people are usually impressed by

monumentality. One day, one of my

professors, Franklin Williams, suggested I look at the work of Jay DeFeo, a Bay

Area artist who had had moderate success on the west coast but was relatively

unknown outside California. Franklin saw a connection between my work and Jay’s

that excited him. Coincidentally, Jay’s work, The Rose, was crated up in one of

the seminar rooms at The San Francisco Art Institute where I was studying. Due

its thickness, the painting was falling apart and SFAI was keeping it safe

until the money could be raised to restore the legendary painting. Jay DeFeo’s

spirit hovered around me.

Franklin

told me the story of The Rose: in the late-fifties to mid- sixties, DeFeo spent

almost all of her time secluded in her San Francisco apartment doing pretty

much nothing but drinking gin, smoking cigarettes and painting The Rose,

obsessing over it and building it up thicker and thicker until the painting

became so heavy that the person who lived below her had to prop up the ceiling

with pillars to keep it from caving in. In the end, the painting, which

measured twelve feet tall by ten feet wide and a whopping thirteen inches

thick, tipped the scales at about 3000 pounds. When SFMOMA took the painting

for an exhibition, they had to remove a window from Jay’s apartment and use a

forklift to get it out. The story mesmerized me in all its romantic, beatnik

glory. Here was someone I understood and who I assumed would understand me. At

the time, I didn’t see how sad a story the making of The Rose actually was; to

me, it was tragic but cool. At that

point in my life, I was not equipped to understand how truly sorrowful Jay’s

life must have been. Franklin gave me a reproduction of the The Rose. I remember it well: a large yellowed foldout

card with the image of the Rose on the front and text on the interior. I was

fascinated with the image - the massive sculpted painting appeared to stand on

its own, it was so thick, yet, despite the obvious materiality, the painting

appeared positively transcendent.

Jay DeFeo

The

Rose

1958-66

oil with wood and mica on

canvas

327 x 234

cm

As

it turned out, Franklin and Jay were friends and he wanted me to meet her. She

was having a birthday party at her home in West Oakland and Franklin invited me

to attend. It was an important birthday, not only because Jay was turning 60

but also because she had been diagnosed with lung cancer the previous year. I

agonized over what to buy her and walked through some of the worst streets of

Oakland to get to her loft. When I finally arrived, a young man who seemed

quite surprised to see me greeted me at the door. Franklin had given me the

wrong date. I had missed the party by one day and therefore missed meeting

Jay.

The

next time I saw Franklin, he still seemed intent on my meeting Jay and told me

that he would drive me out to her place one day – that he would arrange

everything. In the meantime, Jay’s cancer worsened. She passed away on November

11, 1989 before we had a chance to meet.

In

1995, The Whitney Museum held an exhibition called “Beat Culture and the New

America: 1950-1965”. It was the first time The Rose had been exhibited on the

east coast and the first time it had been shown since it was crated up and

stored at SFAI. At the time of the exhibition, I was quite ill and just a few

months away from my own diagnosis of cancer; another parallel development in

our lives. It was the first time I had

ever seen the Rose in person. It was magical.

Since

then, I have seen the painting at least four times and have seen several

exhibitions of her work at SFMOMA and The Whitney which purchased The Rose

after the beatnik exhibition. Interestingly, as my own work has evolved and

grown exponentially, I have seen that the connection between my work and Jay’s

goes far beyond the monumentality of my early work. We share a great love for

edges. De Feo’s collages and late paintings have a quiet sparseness and utilize

crisp contours as a way of creating figure/ground reversals and pushing and

pulling space. She also had a love of technology. There is a peculiarity to her

work, something that made her work uniquely hers and not a part of any particular

artistic movement. Her work is disturbing yet it is also beautiful.

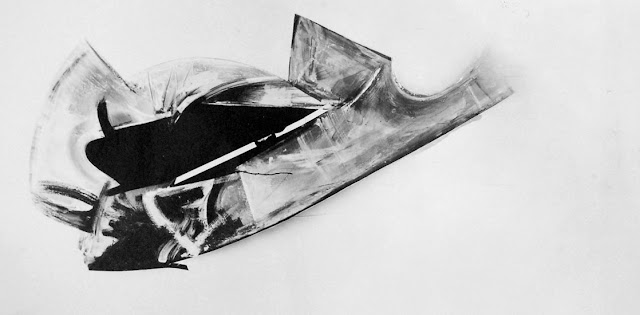

Jay DeFeo

Loop

System: Where the Swan Flies

1975

acrylic mixed media

122 x 244

cm

There

was a time when I had a hard time looking at The Rose. It seemed to me Jay had

bared her soul for the whole world to see her psychological flaws. The painting

seemed mostly an expression of a tortured woman’s perfectionistic nature and obsessive/compulsive

tendencies. It seemed naïve and too exposing. As time has gone on, however, my

feelings about Jay’s work have continued to evolve. I still think The Rose is

an amazing work of art, in my mind singular in its scale, its presence and it’s

spiritual impact. As opposed to when I was younger, however, what is remarkable

to me now about the painting is not how big, thick and imposing it is. What I

find incredible and unique about The Rose is that while the painting takes the

physical form of an utterly exposing manifestation of pure pathological

neuroses it manages to transcend that level of expression to arrive at

something expansive, infinite and joyously liberating. I like to think that

creating The Rose played that same role for Jay in her own life.

Suzanne Laura Kammin, 2015

Return

Of The Master

2015

oil on linen over panel

No comments:

Post a Comment